Data modeling

To paraphrase George Box's aphorism, "all data models are wrong, but most are useful." In other words, all data models are inherently imperfect, but their value lies in their utility, not in their perfection.

Previously, Alfred Korzybski had noted in 1933: "A map is not the territory it represents but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness." The analogy of city maps is used to explain that models, like maps, serve practical purposes despite their limitations. The same is true for the blueprints used in building architecture, especially when considering their role as simplified representations of complex real-world systems, and in communications between the different stakeholders of the project: owner, architect, building contractors, workers, etc.

Maps, blueprints, and data models are abstract representations of complex physical systems designed to guide understanding and implementation. Architectural or engineering blueprints simplify physical structures by omitting imperfections, assuming ideal conditions, and standardizing variables. Similarly, data models abstract real-world information systems by focusing on key concepts, how they relate to each other, and the business rules, while ignoring certain operational or contextual nuances. All data models, therefore, are inherently "wrong" in the sense that they are incomplete or approximate; they cannot fully capture every data anomaly, user behavior, or dynamic change in business processes.

Yet, like maps and blueprints, data models are immensely useful. Data models are abstract representations of data structure and content. They serve as a shared language between stakeholders - analysts, developers, and business users - facilitating communication, planning, consistency, and governance. They help estimate complexity, ensure compliance with standards, and provide a structured foundation for building reliable, scalable information systems.

Data Modeling

Data modeling is the process of constructing data models.

It's essential to emphasize that pragmatism is key in the data modeling process. Data modeling has sometimes earned a negative reputation due to a perceived disconnect from its core objectives. The goal of data modeling is not to become a roadblock, but to support the broader mission of delivering value. It should be approached with two main purposes in mind:

1) to produce schema or data contracts, in the form of DDLs, schemas, scripts, and other artifacts, to ensure clear communication between data producers and consumers;

2) to contribute to metadata repositories, allowing the data community -- from business users to technical teams -- to share a common understanding of the data's meaning, context, and usage.

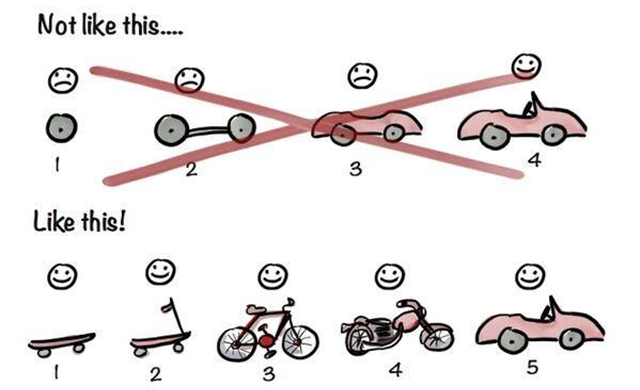

Moreover, the process must be agile, delivering added value early and iteratively, allowing for continuous improvement and adaptability as requirements evolve.

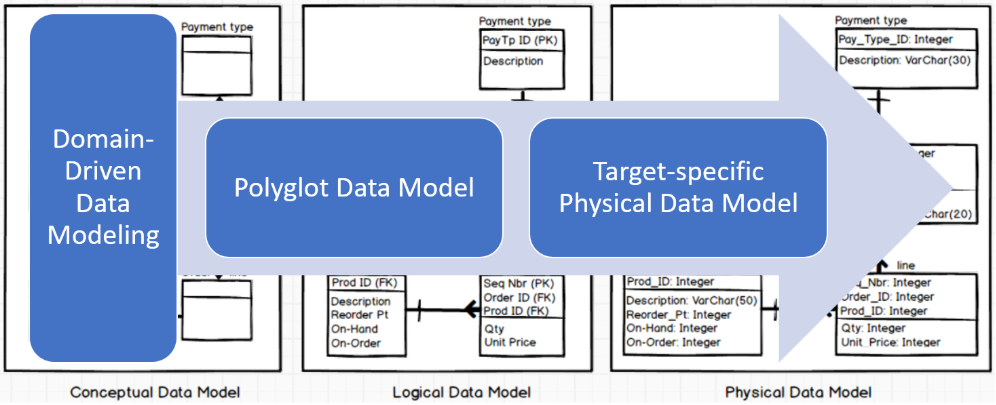

We advocate for a methodology we call Domain-Driven Data Modeling, which helps avoid the pitfalls of large, monolithic enterprise data models. By breaking down complex models into smaller, more manageable modules, this approach enhances clarity, scalability, and maintainability. To support this methodology, we developed Hackolade Studio around a modular architecture where any model or part of a model can be defined independently and then reused elsewhere. Through references, components of one model can seamlessly integrate into others, promoting consistency and efficiency across the data architecture.

More formal processes are well documented, including in the Data Management Body of Knowledge.DMBoK2.

Data models levels of details

There are three traditional levels of data modeling - conceptual, logical, and physical - serving distinct purposes, each with increasing levels of detail and technical specificity.

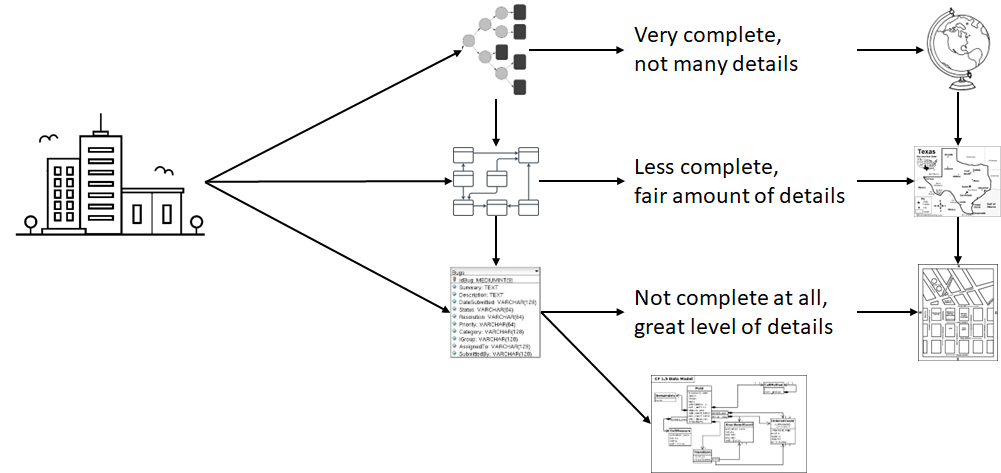

Conceptual data modeling is the highest level of abstraction, focused on reaching consensus on vocabulary, and defining the core business entities and their relationships - without considering how the data will be implemented. It’s like the early sketches of a building, meant to align stakeholders on the big picture and ensure a shared understanding of the domain. Or like a globe, as the conceptual model provides a complete, high-level overview of the domain. It shows all major “landmasses” (key business entities) and how they relate, but without fine detail. Its objective is the broad understanding and alignment across stakeholders.

Logical data modeling adds more structure and details, specifying attributes, data types, and relationships in a technology-independent manner. It is similar to a detailed architectural plan that includes room dimensions and functional layouts, serving as a bridge between business understanding and system design. The logical model is also like a detailed travel map: it doesn’t show everything, but it adds structure and granularity such as cities, highways, and regional boundaries. Similarly, the logical model includes attributes, relationships, and rules without being tied to a specific technology, offering a clear, detailed representation for design.

Physical data modeling translates the logical model into a model tailored for a specific database system or data exchange mechanism, incorporating performance considerations such as indexing, partitioning, and storage formats. This is the engineering drawing ready for construction: precise, technical, and implementation-ready. The physical model is also like a city street map, showing exact routes, intersections, and infrastructure. It reflects how the data will actually be stored and accessed in a specific database system, with details like column types, indexes, keys, and performance optimizations.

Together, these models form a layered blueprint that evolves from broad business concepts to deployable database structures and data exchanges.

| Purpose | Traditional | Hackolade Studio |

|---|---|---|

| Align | Conceptual | Polyglot graph |

| Refine | Logical | Polyglot ERD |

| Design | Physical | Target |

When combined with Domain_Driven Data Modeling, you will see that Hackolade Studio blurs the lines of the traditional conceptual-logical-physical modeling: